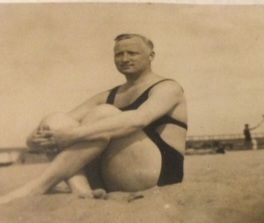

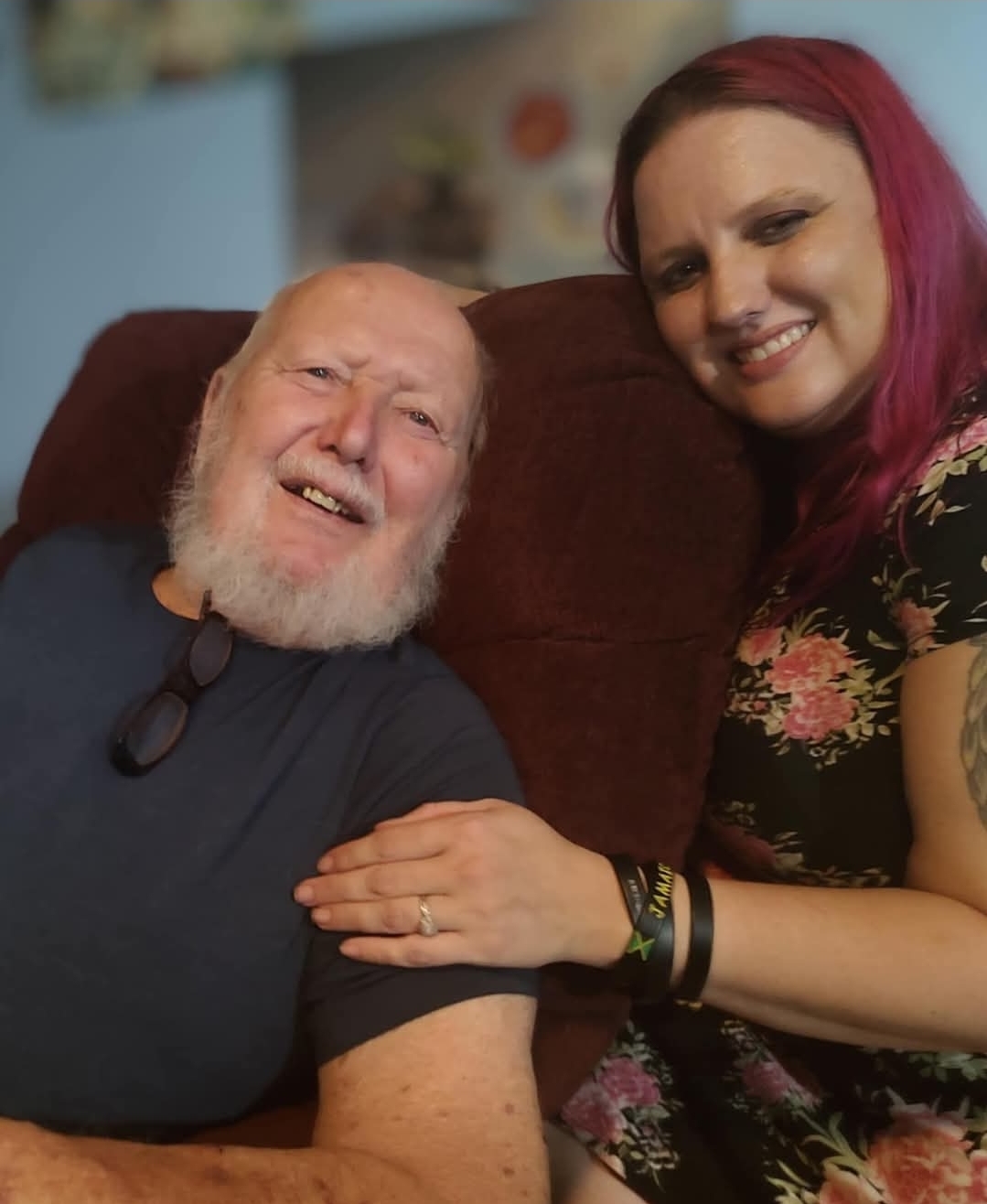

If you have ever met my father, chances are you have probably heard at least part of this story. I’ve probably heard it a thousand times, and it never stops drawing me in. Trying to imagine what happened that day. Rereading the story in my father’s book this morning, tears filled my eyes. It never get’s easier to read, it never gets easier to hear.

This is the terror that is war.

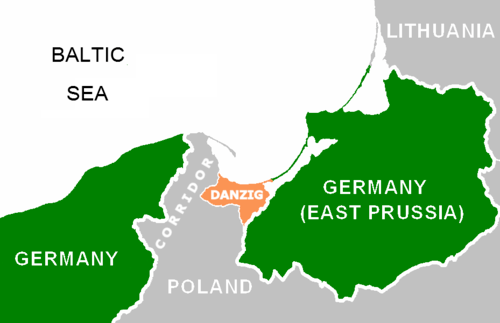

“Hitler’s army was in retreat. More and more Refugees had flooded Danzig seeking passage across the Baltic Sea. Thousands attempted to cross the icy waters seeking safety, only to either drown or be torpedoed by Russian submarines. By land the Russians were pushing the German front closer and closer. The sound of distant gunfire, soon became louder and more regular.

Hitler had declared that Danzig would be a fortress defended to the death. Despite Nazi propaganda that attempted to convince the German public they were still winning, Mutti had decided that it was no longer safe for our family to stay in the city, and she worried to find a safe way for us to leave.

One night, we were awoken by the sound of Mutti’s voice, “Get Up! Get Dressed, we have to leave in 10 minutes!” Startled we awoke and Mutti instructed us to put on layer after layer of clothing. Two pants, double sweaters, layers of socks, a thick jacket. I could hardly more. What is going on?

Hurriedly, she shoved things into our rucksacks. Canned goods, socks, water, a roast that had interestingly enough showed up after my pet rabbit had gone missing. My backpack had also been stuffed with the few pieces of silver that remained not buried in the back yard. Fearing anything she carried may have a greater chance of being stolen or taken by the Nazi Army or others, she had entrusted our valuables on the back of her youngest child.

It was heavy and uncomfortable. We wished we didn’t have to carry the packs, but Mutti insisted. Within a few minutes, Mutti rushed us out into the streets and towards the train station. She had been given top secret information from her connections in the military that there was a special train authorized to leave the city for military families, and there would be a compartment for SS Officers wives and children.

This was to be our escape as the Russian fighting was sure to soon reach within the city limits. It was pitch black, and 8 or 10 inches of snow was freshly fallen on the ground. I started to complain that I was freezing and tired, but brother Gottfried poked at me and reminded me to be tough and strong to make Vati proud.

The alley on our way to the train station was lined with the abandoned wagons of yesterday’s refugees. In the darkness, my feet tripped on something big and bulky under the snow. Was that a person frozen? Is that what that was? Before I had time to process what I had just seen, brother Gottfried pulled my hand and told me to hurry up, half dragging me a long the way. I pulled it together and quickened my pace, I wouldn’t want to disappoint Vati.

As we arrived at the train station we were in total disbelief of what we were seeing. A sea of people flooded the platforms, thousands jammed as far as the eye could see. Mutti pushed us off of the sidewalk and along the train tracks, hoping to move more quickly through the crowd. I stumbled and fell trying to traverse the uneven tracks below me, scraping my knee but tried not to cry. I remembered Gottfried’s earlier warning about how I needed to be tough.

Sucking up my tears, we moved closer. A train could be heard in the distance, and strangers from the crowd reached out their hands to lift us out of the way of the incoming train as it arrived. There were so many people. I wondered how many trains it would take to fit everyone.

All of a sudden a whistle blew and a large steam locomotive started pushing some express railroad cars backwards into the station. The crowd surged forward. People were pushing and shoving, rushing towards the doors. The only thing keeping my brother and I from being pushed back down into the tracks was a cast iron lantern near the tracks.

Mutti screamed at us to hang on and not let go. Gottfried and I ducked down under all the people and hung on with all of our might. As the train slowed to a stop, we saw that the compartments already looked full and the doorways were nowhere near us. As we watched and felt the people pushing towards the doors, it began to set in that there was no chance we were going to get on.

Suddenly, in the midst of all of the madness around me I felt my Mutti’s strong arm around me. She grabbed me, and hoisted me up towards the window of the train car. From here, a bandaged soldier grabbed me and pushed me up further into the overhead luggage compartment in the train car. A few moments after, my brother was pushed through the same window and placed on a small table attached to the wall below.

Now people were coming in through the door, filing in beneath and around us until there was not even the tiniest space in the train car left to move. I started to scream for Gottfried, and he reached up his hand to grab mine, as if to say it’s going to be ok. “Mutti! Mutti! Mutti!,” I screamed and cried. Where was Mutti?

The stench of urine and sweat filled the air around me. My brother and I looked over and over the people jammed into the compartment with us looking for our mother, but she was nowhere to be found. Our cries to her went unanswered. We tried asking the other passengers over and over had they seen our Muttti. “Where was Mutti? Mutti!”, I cried over and over as I searched the crowd below me. The whistle blew and soon our repeated cries out for our mother were being drowned out by the rhythmic chug of the wheels turning as the train pulled farther and farther away from the station and those who had been left behind, some still desperately clinging to the windows and doors as it pulled away.

Mutti was nowhere to be found.

This was the first time I learned that fear had a smell.” – Jochen

Even as I sit here, retelling the story I’ve heard a million times, my eyes still swell with tears. I try to imagine my Uncle and Father being shoved through that window. Imagining the choice that my Omi had to make in that moment. Stay with her children and risk them being left in Danzig by the train or shove them through a train window in the hopes that by doing so, at least they would survive and get out before all was lost in Danzig.

Can you imagine? The love it takes, the strength it takes, to make a decision like that.

Can you imagine the fear my father felt? His mother gone. Him not knowing where they were going or why they were going. Not knowing if he would ever see his Mutti again. Pushed into a luggage compartment over a sea of strangers, with only his brother’s hand to give him comfort at that time.

It’s heartbreaking. It’s cruel. It’s wrong that he and his brother, or anyone else on this planet for that matter should have to experience something like that. When the war in Ukraine began a few years ago, there was a black and white picture that circulated social media of a train station jammed packed with thousands of people trying to escape the Russian attacks. The caption, “History is Repeating Itself”, went along with it.

This picture was fact checked, and it was indeed a picture of the people of Ukraine fleeing the war with the Russians, just changed to black and white.

When my father saw this picture, it broke him. It brought back every single moment of that harrowing ordeal that he and his brother went through that day. He knows more than anyone what it feels to be in that crowd, to be one of those people. Just wishing and praying you escape the war and find a way to survive.

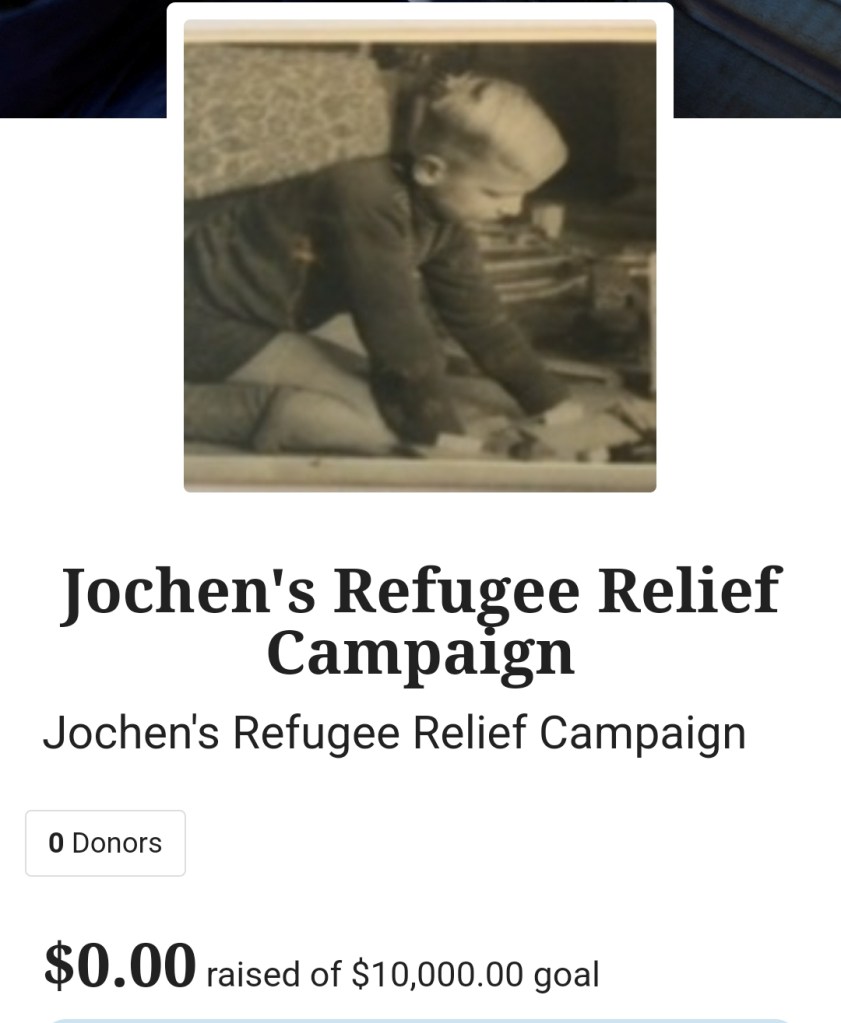

I’m proud to say, that the photo became a call to action for him. He has since used that photo along with his story in order to fund raise for Ukrainian Refugees raising over $6,000 through his church and a local community group. Selling Schnitzel dinners to fund raise for Refugees, making the meals himself at 87 years old.

No one should have to go through such a traumatizing experience as having to flee your home due to war. Sadly, today, refugees are sometimes depicted as being a drain on society. People who have never experienced the horrors of war first hand make snide remarks and judgement calls about mothers trying to do anything it takes to keep their children safe.

I think the most important thing this story does, is it puts a face to the refugee. It tells a first hand account of what one might experience fleeing from war. And if you know my father, it also shows that the “poor refugee” can go on to become an incredible person. A valuable member of society. A person with so much to give, that wherever he landed would one day be blessed with his having been there.

Refugees are people. Real, living, breathing, loving, hard working people. They deserve love, and kindness and empathy. They deserve compassion. The stories they tell could break even the strongest heart.

If his story touched you, and you are interested in donating to refugee families in need, I have created a fundraising campaign for this in his honor. It doesn’t need to be much, even enough for a “Shnitzel Dinner” would be fine. Children don’t deserve to experience what he has, so every penny raised will be a blessing as families try to rebuild and recover.

https://unrefugees-ukraine.funraise.org/fundraiser/jochen’s-refugee-relief-campaign

He doesn’t know I’m doing this. Or at least he won’t know until he reads this. But I figure this is one of times where I figured it was better to ask for forgiveness rather than ask for permission.

Please read, share, and subscribe to hear more of his incredible life stories. And if you donated a “Shnitzel Dinner” please let us know so we can thank you. Love, Verina