We are hopping back across the ocean and back in time for this week’s episode. As I mentioned in the beginning, this blog will not always go in order. Eventually, I hope to use these stories in the composition of a book which I promise will be in a more chronological order, but for now excuse us for bouncing around as we tell our story.

So, grab a coffee, cozy up, keep the tissues nearby, and let’s dive back in to the events that led to my father to become listed as a “displaced person” the first time.

Take a trip with us back to Berlin, January 1945.

“We had made it out of Danzig on the train, but we were not yet out of danger. The Russians were steadily advancing in that direction from Poland, and the threat of nightly air raids were constant from the Allied Forces. Fortunately, once again Mutti heard of another train that would be departing Berlin for mothers with children. We could not believe our luck, until we saw the train.

The train was made up of only a few cattle cars, nothing like the regular train cars that we were used to riding in. I remembered seeing similar railroad cars arriving at the prison camp in Stutthof, Poland when we had traveled to spend time at our Uncle’s farm in East Prussia. Nervously, we were loaded into the cars, while the engineers and conductors checked to make sure each car had at least 50 people. The small ventilation windows along the top of the car had barbed wire nailed over them, which frightened me, but there was no other choice. The conductor suggested we find a spot with a lot of straw, that we could use for bedding.

Over the next five days we would slowly travel across the German countryside, stopping only to find food and avoid attacks from the Allied Forces. We had only a bit of straw beneath us for our bed and later a tin can which became a chamber pot when Mutti was unable to leave the train car to use the bathroom.

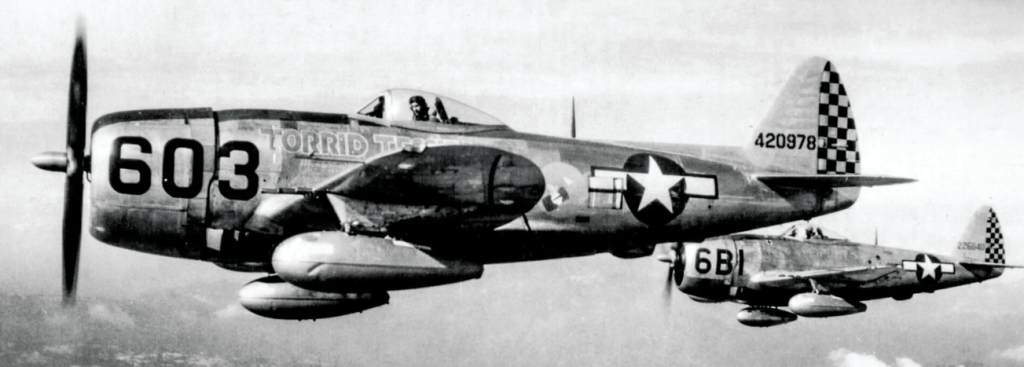

The doors to the cars were kept open at all times, so that when under attack, we could quickly hop out and run for cover. This was a frequent occurrence, and during one of those occasions a French fighter plane began making passes targeting the train with machine gun fire. We jumped and scrambled to find cover, Mutti screamed and crawled next to us behind the large wheels of the train. We cried at the clatter of the machine gun thinking Mutti had been hit. She assured us she was fine and had only sprained her ankle. I pressed myself as low as I could on the ground behind the rail. As the clattering above continued, I felt a sharp sting on my back, but too much was happening to give it any much thought.

Once the immediate danger had passed we hopped back into the cattle cars and continued on our way. It was not until the following day as I was undressing that I found a large bloodstain on the back of my shirt. Shrapnel from the machine gun fire was lodged in my back, and to this day I still have the scar. I was scared, but since I didn’t feel much pain from it, I kept quiet about it so as not to add to the problems Mutti had to worry about with her injured ankle.

After 3 days of starving with no food, the conductor stopped the train as we were passing fields of beets and carrots, and Gottfried and I ran and gathered whatever we could as quickly as possible to take back to the train to eat. We had to be quick and stay close to make sure that we would not be left behind if it began moving again without notice.

We could no longer safely travel during the day once we left the countryside. The risk of attack became too great, so we traveled under the cover of darkness once we reached the industrial parts of Germany. One day as we waited, my brother and I cleaned out Mutti’s chamber pot as best we could and having cut up the beets and carrots we found earlier, cooked a stew using water that dripped from the train engine. This warm meal greatly impressed our mother despite having a lingering taste of engine fluids which I will never forget. We had made a fine feast as we neared the end of this tumultuous journey.

The trip that normally took 7 hours to travel from Berlin to Gmund an Tegernsee by train, ended up taking us 5 days. By the time we arrived, Mutti’s hair had turned from dark brown to stark white. She was 38 years old. It would remain white the rest of her days. – Jochen

Full disclosure, I had to stop and take a break less than a third of the way into writing this story for about half an hour to compose myself. I know this story, I’ve read and heard these words, but having to put my father’s experiences in my own writing is different. It’s hard to write his story without putting myself in his place, picturing each event and trying to think of how it must have been like.

But today it wasn’t his story that got to me. It was the others. The ones who came before. The ones who didn’t live to tell their stories. I looked over my Dad’s emails, and reread the pages of his book, and couldn’t get past the description of the Cattle Cars with Barbed Wire windows. I went to the kitchen and wept.

How do you tell the story of how your father had to travel in the same cars where thousands were taken to their death camps? How do I explain their struggle without acknowledging the fact that for as horrible as they had it in World War 2, they were the lucky ones? These cattle cars would take them through incredibly dangerous scary traumatizing experiences, but it is nothing in comparison to the people who were taken to the camps. My father’s beautiful blue eyes and blond hair and strong German heritage was his ticket to be given a chance to survive.

While my father, uncle, and Omi narrowly escaped attacks by both the Allied Forces and the Russians, millions of Jews were killed by the Nazis. In addition to the Jews that most learn about, also homosexuals, black people, people with disabilities, ethnic Poles, Roma, Soviet POW, and people who opposed the Nazi Regime were also imprisoned and executed in mass events.

Over 60,000 people were killed at Stutthof Concentration Camp which was about 22 km from my father’s hometown of Danzig. It began as a civilian internment camp of non-Jewish Poles, which transitioned into a forced labor camp, and then finally a concentration camp. At the time, my father was totally unaware of what was happening to those who were sent there, as were most Germans. All they knew was that men with machine guns guarded high barbed wire fences, but never what happened beyond those walls.

Please know that in telling this story, I mean absolutely no disrespect to those whose family members suffered far worse fates than my own. They say, “history is written by the victors”. So what happens when your family were children of the ones who lost? Where does my father’s story fit into the pages of the history books and documentaries or does it fit in at all? They only ever taught us about the really evil German men, but I never heard anything about the scared little children or their resilient mothers in school. For this reason, I kept the details of my family’s history hidden for the majority of my life from all but a few of my closest friends, never wanting my father or Omi to be lumped in with the really evil men.

This is my goal for this blog. To tell my father’s story, so that it is not lost, and you have the opportunity to learn more than you were taught in school or on television. To make this blog and the eventual book a document that others can read and learn from. It’s not made up or imagined. It is not anyone’s opinion about what they think or was told happened. Things have not been removed to make any side look better or worse. It is a first-hand account of what it was like to live through and survive World War 2 as a German child. Although I assist with editing and revising his words, I never change any events and the facts of his life and experiences.

We cannot change the past, but we can learn from it, and I hope this helps. Maybe if more people had learned that it wasn’t so black and white, it wasn’t so simple, it didn’t all happen at once, and it wasn’t all over when the war was, we wouldn’t be seeing some of the things we are seeing happening today.

Please let me know if you have questions about anything discussed in this blog. I apologize if these topics are hard to read about and reflect on. I am happy to find out more and ask my father anything not covered in his story. We truly appreciate each and every one of you who takes the time to read. Thank you from the bottom of our hearts!

Leave a comment